This section is based on our work published in Physics in Medicine in Biology1. A preprint can be found here.

Background

It is a grotesque understatement to say that the human brain is complex. Although we are a long way from a complete understanding of the brain, we understand some of its basic functions. Of particular interest is the propagation of electrical signals across synapsis which the brain uses to relay instruction to the body. As electrons flow, there are neural currents that, as Maxwell’s equation show, give rise to magnetic fields.

These biomagnetic fields induced by brain currents are extremely weak (7 to 10 orders of magnitude smaller than the Earth’s field). Despite the seeming hopelessness of recovering such small signal, it is possible and precisely the goal of magnetoencelphalography (pronounced mag-nee-toe-en-sell-ful-ography). Don’t worry if you can’t say it, you have plenty of good company. Since it’s a mouthful, we normally go with its acronym…MEG.

MEG is a non-invasive method to image brain function with high spatial and temporal resolution. This is done by placing an array of magnetometers on the scalp and measuring the magnetic field. As one can imagine, it is difficult to isolate brain fields from those originating externally, i.e., Earth, electrical lines, train passing nearby, etc. Nearly every other source will have a magnetic signature orders of magnitude larger than those induced by brain currents.

Figure 1: Biomagnetic fields from neuronal currents, courtesy of Tom Holroyd

MEG readings are used to explore and understand regions and signatures of function and dysfunction. Since the early 1990s, superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs) have been stalwarts in the world of MEG. Although the technology is mature and well understood, there are a number of practical considerations incentivizing alternate technologies. To start, SQUIDs must be cooled requiring a bath of liquid helium which is expensive and subject to commodity shortages. In addition, Dewar wall thickness sets a lower limit on the proximity of sensors to the scalp. Since the magnetic fields induced by electrical currents in the brain are remarkably weak, any additional separation between source and sensor adversely impacts the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and the ability to localize brain activity. Furthermore, to fit all users, the rigid Dewars are sized to fit large human heads, severely limiting their usefulness on young children.

New Possibilities with New Sensors

Recent advances in total field optically pumped magnetometers (OPM) offer a promising alternative to SQUIDs. They operate at room temperature thus eliminating the need for bulky Dewars and hence can be placed within millimeters of the scalp. For more detail, see an overview here2. OPMs are also capable of measuring weak magnetic fields induced by the brain in the presence of large ambient fields allowing for the possibility of wearable MEG systems outside of laboratory environments.

Since total field OPMs are a nascent technology for biomedical imaging, I’ve collaborated with experts in the field such as Svenja Knappe, Orang Alem, and Jeramy Hughes for a simulation study to determine necessary system specifications including sensor count, sensitivity, and forward model fidelity to accurately localize a single dipolar current in a brain modelled as a conducting sphere.

Project Scope

I joined this project to help find methods for extracting the signal of interest and write software capable of solving an inverse problem from magnetometer data. In addition, I ran simulation studies to establish 1) the number of magnetometers necessary, 2) the sensitivity required, and 3) the accuracy of forward model to accurately localize a single dipolar current using OPMs in a large ambient field.

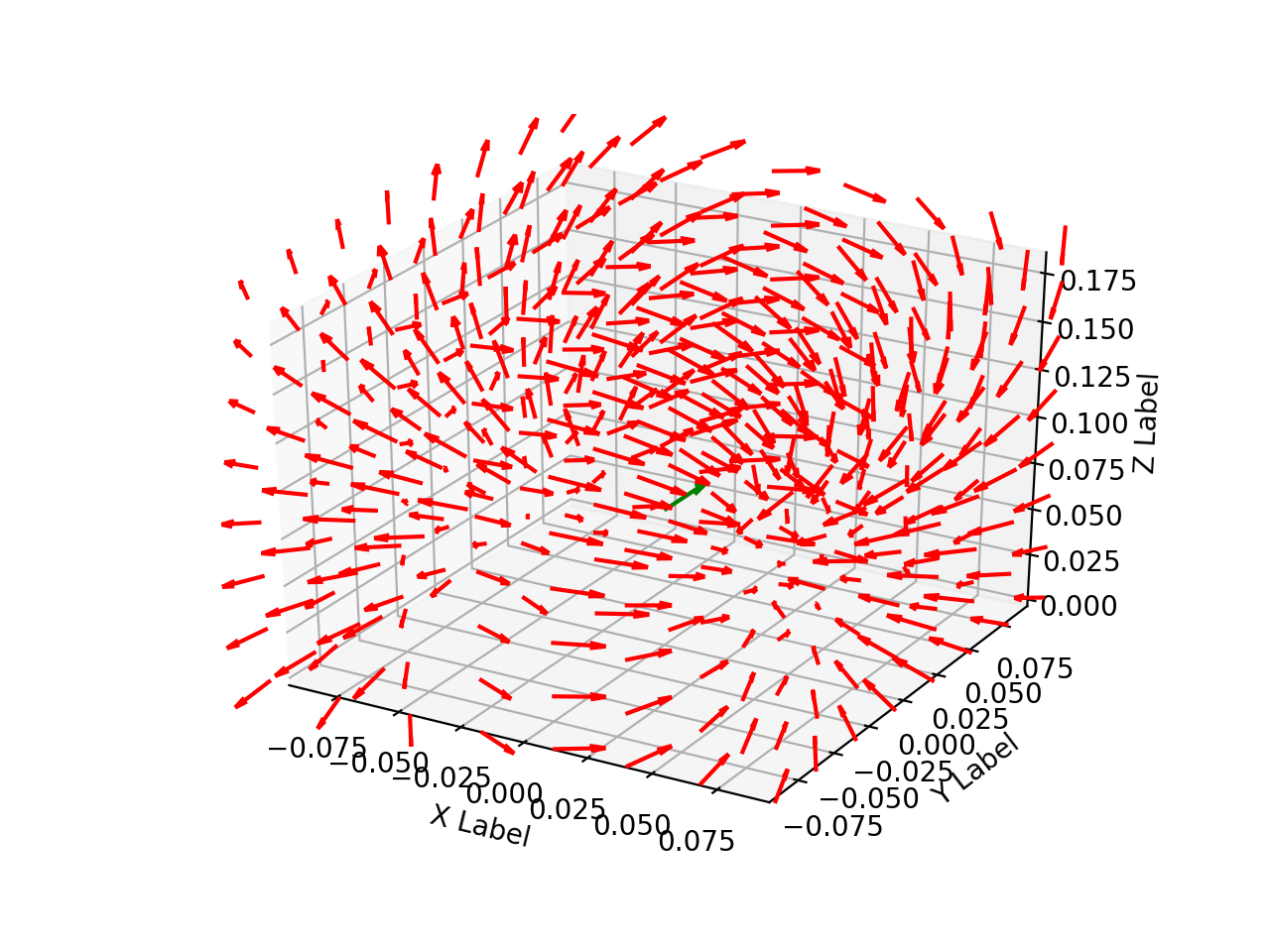

Following the general model for dipole localization in a conducting sphere, the sources are modeled as current dipoles specified by their position, orientation, and magnitude of directional current flow. Current dipoles, which model nearby groups of neurons firing in unison, give rise to magnetic field patterns; these are distinct from magnetic dipoles which can be thought of as small bar magnets. An example field generated by a dipole in a conducting sphere can be found in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Field line orientation induced by a current dipole.

For each set of measurements, the goal is to determine the dipole location and corresponding moment that best explains data recorded with a magnetometer array. We considered static measurements, but our methods can also be used for time series by averaging, peak finding, taking the Fourier transform, and a variety of other processing tools. In what follows, we describe a forward model, explain how it relates to the optimization problem we use for localization, and then outline an algorithm to find sources of neuronal activity.

Forward Model

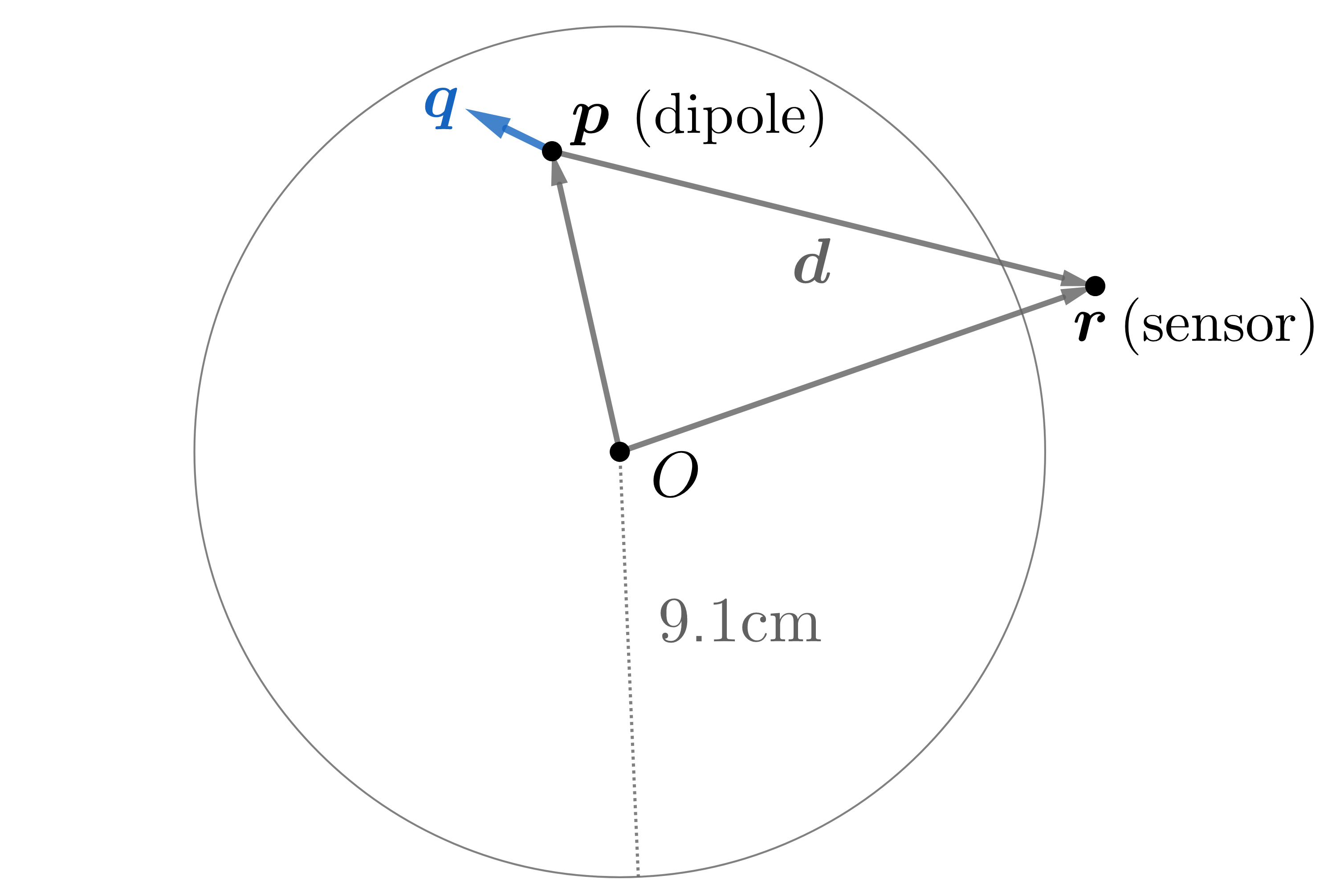

A forward model characterizes the magnetic field of a known source throughout space. We consider the conducting sphere model of radius 9.1 cm provided in Sarvas3

Figure 3: A current dipole gives rise to fields according to a forward model.

It was shown by Mosher, Leahy and Lewis4 that the magnetic field at point \(\mathbf r\) due to a dipole located at point \(\mathbf p\) can be written as the product of a solution kernel, \(\mathbf L (\mathbf r,\mathbf p)\), and the dipole moment, \(\mathbf q\). That is, for a dipole \((\mathbf p, \mathbf q)\), the magnetic field at point \(\mathbf r\) is

\[\mathbf B(\mathbf r, \mathbf p, \mathbf q) = \mathbf L(\mathbf r, \mathbf p) \mathbf q.\]The solution kernel \(\mathbf L\) is given by \(\mathbf L( \mathbf r, \mathbf p) = \frac{\mu_0}{4 \pi} \left[ \frac{ \nabla_{\mathbf p} \Phi \mathbf r^T - \Phi \mathbf I}{\Phi^2} \mathbf C_{\mathbf p} \right]\) with

\[\mathbf C_{\mathbf p} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & -p_z & p_y \\ p_z & 0 & -p_x \\ -p_y & p_x & 0 \end{pmatrix},\]where \(p_x, \ p_y,\) and \(p_z\) are the components of \(\mathbf p\), and \(\mathbf I\) is the identity matrix. Note that \(\Phi \in \mathbb{R}\), \(\mathbf p, \, \mathbf q , \, \mathbf r, \, \mathbf B, \, \nabla_{\mathbf p}\Phi \in \mathbb{R}^3\), and \(\mathbf C_{\mathbf p}, \, \mathbf I, \, \mathbf L(\mathbf r, \, \mathbf p) \in \mathbb{R}^{3 \times 3}\). Defining relative position as \(\mathbf d = \mathbf r - \mathbf p,\) the scalar function \(\Phi\) and its gradient with respect to \(\mathbf p\) are given by \(\Phi(\mathbf r, \mathbf p) = \|\mathbf d\| \left( \|\mathbf d\| \, \|\mathbf r\| + \|\mathbf r\|^2 - \mathbf p^T \mathbf r \right)\) and

\[\nabla_{\mathbf p} \Phi(\mathbf r, \mathbf p) = \left( \frac{\|\mathbf d\|^2}{\|\mathbf r\|} + \frac{\mathbf d^T \mathbf r}{\|\mathbf d\|} + 2 \|\mathbf d\| + 2 \|\mathbf r\| \right) \mathbf r - \\ \left( \|\mathbf d\| + 2 \|\mathbf r\| + \frac{\mathbf d^T \mathbf r }{\|\mathbf d\|} \right) \mathbf p.\]In the absence of clutter, the measured signal, \(y_i\), of a scalar sensor at location \(\mathbf r_i\) will be the norm of the superposition of the ambient field, \(\mathbf a\), and the dipolar field, \(\mathbf B\), plus noise, \(\eta_i\). That is, \(y_i = \| \mathbf B(\mathbf r_i, \mathbf p, \mathbf q) + \mathbf a\| + \eta_i\). We consider cases where the ambient field is sufficiently large such that \(y_i\) is always positive. Since the background fields we consider are many orders of magnitude larger than the biomagnetic signals we aim to measure, i.e., micro vs. femto Tesla, we can treat scalar sensor readings as a superposition of the dipolar and ambient field, \(\mathbf B(\mathbf r_i, \mathbf p, \mathbf q) + \mathbf a\), projected onto the ambient field’s direction. That is, letting \(\hat{\mathbf a}\) be the ambient field’s unit vector, writing \(\mathbf b_i = \mathbf B(\mathbf r_i, \mathbf p, \mathbf q)\) and assuming \(\|\mathbf b_i\| \ll \|\mathbf a\|\), the noiseless scalar magnetic field at \(\mathbf r_i\) is

\begin{align} \label{eq:taylor_approx}

| \mathbf a + \mathbf b_i| \approx |\mathbf a|+\hat{\mathbf a}^T \mathbf B(\mathbf r_i, \mathbf p, \mathbf q) =: f_i.

\end{align}

Thus for an MEG array with \(M\) sensors at points \(\mathbf r_1, \mathbf r_2, ..., \mathbf r_M\), the forward model is

where \(\boldsymbol{1}\) is the vector of ones. This approximation is an affine function of \(\mathbf q\) paving the way for a simplified localization algorithm. Upon testing, we found that the difference between our approximation and the precise forward model, i.e., \(\big| f_i - \|\mathbf a + \mathbf b_i \| \big|\), was below the noise floor used and therefore negligible. By using a reference sensor that picks up the background field \(\mathbf a\) away from the biomagnetic sources, we can subtract out the ambient field. This is a basic form of gradiometry. For ambient sources that vary more quickly over shorter length scales, more complex gradiometry can be applied. With a forward model and data at our disposal, we can now formulate the optimization problem to localize a dipole.

Optimization Problem and Algorithms

Given the forward model \(\mathbf f\) from above, the goal is to find a dipole \((\mathbf p, \mathbf q)\) that best explains observed MEG data \(\mathbf y\). Here, we assume that \(\mathbf a\) has been removed from the signal and that

\[\mathbf A = \begin{bmatrix} \hat{\mathbf a}^T \mathbf L(\mathbf r_1, \mathbf p) \\ \hat{\mathbf a}^T \mathbf L(\mathbf r_2, \mathbf p) \\ \vdots \\ \hat{\mathbf a}^T \mathbf L(\mathbf r_M, \mathbf p) \end{bmatrix}\]We formulate this mathematically with the non-linear least squares problem

\[\min_{\mathbf p,\mathbf q} \ \| \mathbf f (\mathbf p, \mathbf q) - \mathbf y \|^2 =\min_{\mathbf p, \mathbf q} \ \|\mathbf A (\mathbf p) \, \mathbf q - \mathbf y \|^2\]which is convex in \(\mathbf q\) but not in \(\mathbf p\). To address non-convexity, we break the problem into two parts as outlined in Brain Signals5. First, we find a point that is in the global optimum’s basin of attraction as a warm start, then employ an iterative nonlinear solver.

For the warm start, we grid the variable \(\mathbf p\) over the sphere’s interior at \(K\) locations. For each grid value of \(\mathbf p\), the optimal value of \(\mathbf q\) is easily found by solving an ordinary least squares problem, so \(\mathbf q\) does not need to be discretized. In particular, at a fixed grid point \(\mathbf p = \mathbf p_k\) with \(k \in\{1,\ldots,K\}\), the optimal solution \(\mathbf q_k^*\) to the above optimization problem is

\[\mathbf q_k^* = \big( \mathbf A(\mathbf p_k)^T \mathbf A(\mathbf p_k) \big)^{-1} \mathbf A(\mathbf p_k)^T \mathbf y_g.\]After finding location/moment least square pairs, \((\mathbf p_k, \mathbf q_k^*)\), for all \(K\) discrete locations, the optimal index \(o\) is given by

\[o = \underset{k\in\{1,\ldots,K\}}{\text{argmin}} \ \|\mathbf A (\mathbf p_k) \, \mathbf q_k^* - \mathbf y_g \|^2.\]Hence, we use pair \((\mathbf p_o, \mathbf q_o^*)\) as a warm start for a continuous optimization algorithm. In our simulations we used L-BFGS6 as the continuous optimization algorithm, which is a quasi-Newton method, although others could be used. L-BFGS iterates through the space of possible values for \((\mathbf p, \mathbf q)\) to find a fit minimizing residual error.

-

Clancy, Richard J., et al. “A study of scalar optically-pumped magnetometers for use in magnetoencephalography without shielding.” Signal Processing 66 (2021): 175030. ↩

-

Knappe, Svenja, Tilmann Sander, and Lutz Trahms. “Optically-pumped magnetometers for MEG.” Magnetoencephalography. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014. 993-999. ↩

-

Sarvas, Jukka. “Basic mathematical and electromagnetic concepts of the biomagnetic inverse problem.” Physics in Medicine & Biology 32.1 (1987): 11. ↩

-

Mosher, John C., Richard M. Leahy, and Paul S. Lewis. “EEG and MEG: forward solutions for inverse methods.” IEEE Transactions on biomedical engineering 46.3 (1999): 245-259. ↩

-

Ilmoniemi, Risto J., and Jukka Sarvas. Brain signals: physics and mathematics of MEG and EEG. Mit Press, 2019. ↩

-

Liu, Dong C., and Jorge Nocedal. “On the limited memory BFGS method for large scale optimization.” Mathematical programming 45.1 (1989): 503-528. ↩