Background

Optimization is concerned with the minimization of an objective or cost function, \(f: \mathbb R^n \rightarrow \mathbb R\), and is cast mathematically as

\[\min_{x \in \mathcal C} f(x)\]where \(\mathcal C\) is a generic constraint set. For many problems, the objective and/or constraints are too cumbersome for a solution to be computed analytically. In such cases, we turn to numerical optimization methods.

In numerical optimization, the objective function is minimized iteratively. This is done by stepping through the function domain and choosing a descent direction at each point. Gradient descent, as the name suggests, does so by moving in the direction opposite the gradient at each iterate. The step-size is specified by the “learning rate” which is usually set by the user. Although the negative gradient is guaranteed to be a descent direction when it exists, it is possible to step too aggressively and realize a function increase. Barring strong assumptions like Lipschitz continuity, it is difficult to choose the step-size in a principled way.

There are two broad approaches to address this: line-search and trust region methods. A line-search method choose a descent direction then evaluates the objective at different points along the ray until a sufficient reduction in the cost is observed. The method is intuitively simple and easy to implement. Unfortunately, in some applications such as PDE constrained optimization, a single function evaluation can be prohibitively expensive. Evaluating the objective numerous times for a single iteration is undesirable.

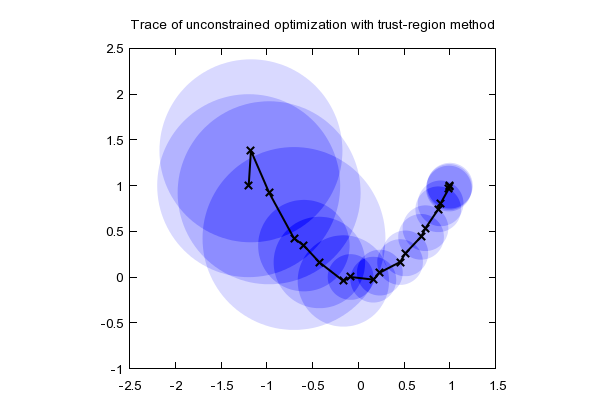

Trust region methods circumvent multiple function evaluations per iteration by maintaining a set over which an easily computed model serves as a good approximation. At the current iterate, \(x_k\), a model function, \(m_k(\mathbf p)\), is formed where \(\mathbf p\) is the displacement vector from the current iterate. A popular choice of a model is the second order Taylor expansion, i.e., \(f(\mathbf x) \approx m_k(\mathbf p) = f(\mathbf x_k) + \mathbf p^T \nabla f(\mathbf x_k) + (1/2) \mathbf p^T \nabla^2 f(\mathbf x_k) \mathbf p\). The model is optimized over (constrained by) the trust region and is known as the trust region subproblem. A simple model combined with a simple constraint results in a subproblem that is easy to solve. If a sufficient decrease is realized, the next iterate is chosen to be \(\mathbf{x_{k+1} = x_k + p_k}\).

Figure 1: Trust region progress over several iterations. Courtesty of Ye Wenhe

This is performed iteratively until a minimizer is found. The algorithm is given by:

Trust region algorithm

- Input \(\mathbf x_0, \ \eta_{good}, \ \eta_{great}, \Delta_0, \gamma_{inc}, \gamma_{dec}\)

- For \(k = 0, 1, 2, ..\), loop until converged

- Solve the trust region subproblem \(\mathbf p_k = \text{argmin}_{\mathbf p} \ \ m_k(\mathbf p) \ \ \text{such that }\| \mathbf p \| \le \Delta_k\)

- Calculate \(\rho_k = \frac{f(\mathbf x_k) - f(\mathbf{x_k + p_k})}{m_k(\mathbf 0) - m_k(\mathbf{p_k})}\)

- If \(\rho_k > \eta_{good}\)

- Accept step: \(\mathbf {x_{k+1} = x_{k} + p_k}\)

- If \(\rho_k > \eta_{great}\)

- Expand trust region: \(\Delta_{k+1} = \gamma_{inc} \Delta_k\)

- Else

- Keep trust region fixed: \(\Delta_{k+1} = \Delta_k\)

- Else

- Use last iterate: \(\mathbf{x_{k+1} = x_k}\)

- Shrink trust region: \(\Delta_{k+1} = \gamma_{dec} \Delta_k\)

- next \(k\)

Variable Precision Trust Region Methods

The work in this section is based on our preprint, “TROPHY: Trust Region Optimization Using a Precision Hierarchy”.

We consider the model \(m_k(\mathbf p) = f(\mathbf x_k) + \mathbf p^T \nabla f(\mathbf x_k) + (1/2) \mathbf p^T \mathbf H_k \mathbf p\) where \(\mathbf H_k\) is an approximation for the Hessian and assume that the function and its gradient are expensive to compute. This setup is typical for PDE constrained and large-scale optimization. Since it can take hours to compute a single function/gradient pair, we’d like to evaluate them as infrequently as possible. Under such conditions, line-search methods are undesirable since they may require calling the objective many times for a single iteration. Trust region methods are a natural choice.

Given the computational burden associated with calling the function, we would like to find ways to reduce the cost. Although double precision is standard for scientific computing, there are many situations where the additional accuracy is unnecessary. Furthermore, new hardware including GPUs and TCUs natively support lower precision types such as single and big float halfs which can significantly reduce computational, communication, and storage costs as well as power consumption. In work with Jan Hückelheim, Matt Menickelly, Paul Hovland, and Krishna Narayanan of Argonne National Laboratory, we investigated the use of switching precision when necessary to reduce the computational load.

To further reduce the cost for large scale problems, we used a limited memory symmetric rank-1 update for the approximate Hessian. This allowed us to implement a matrix-free Hessian-vector product to keep the linear algebra cost on the trust region subproblem low. Preliminary results are promising showing a reduction in cost assuming that single (half) precision evaluations can be computed for 1/2 (1/4) of the cost required for double precision.

TABLE: Wind field retrieval example

| Run | # its | Half calls | Sing calls | Doub calls | Adj calls | Fun val | Grad 2-norm | Grad inf-norm | Success |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single avg | 3410 | 0 | 3411 | 0 | 1706 | 0.005263138 | 0.000950775 | 3.96E-05 | TRUE |

| Double avg | 1876 | 0 | 0 | 1877 | 1877 | 0.0045012 | 0.00090924 | 3.75E-05 | TRUE |

| Dyn avg | 2362 | 465 | 1898 | 6 | 1071 | 0.004732105 | 0.000942858 | 4.01E-05 | TRUE |

Performance of variable precision algorithm versus single and double precision implementation. Stopping criteria \(\| \nabla f(\mathbf x_k) \|_2 < 10^{-3}\)

We note that in the above example, the adjusted number of calls is based on a double, single and half precision evaluation costing 1, 1/2, and 1/4, respectively. Our dynamic precision algorithm performs well offering an encouraging proof of concept.

Hermite Interpolation Methods

Similar to the previous section, we consider the case where gradient evaluations are expensive or only available intermittently. This might be the case if using finite difference approximations or when using a multi-fidelity framework. With limited availability of derivatives, the derivative free optimization (DFO) framework seems appropriate. DFO methods have seen considerable interest over the past several years given their ability to handle non-differentiable objectives arising in machine learning and data science applications. The classical approach is to construct a model function \(m_k(\mathbf p)\) for the TR subproblem using an interpolating polynomial rather than a Taylor expansion. Taylor series are popular since they provide optimal local information such as the direction of steepest descent and curvature, but provide limited knowledge outside the immediate neighborhood barring strong assumptions.

Interpolating polynomials

Interpolation methods track previous function values providing more information about the objective’s general behavior. Accordingly, weights are chosen such that \(m_k(\mathbf 0) = 0\) and \(m_k(\mathbf p_i) = f(\mathbf x_k) - f(\mathbf x_i)\) for up to \(\frac{n(n-1)}{2}\) previous function values. We center the interpolating function to simplify calculations. Using these interpolation conditions, we can compute weights to find the interpolating polynomial to use in the trust region subproblem.

For example, consider a two dimensional problem of variables \(\mathbf p^T = [x, y]\). Our form for the model is \(m_k(\mathbf p) = \mathbf{g^T p} + (1/2)\mathbf{p^T \ H \ p}\) which can be expanded element-wise as

\[m_k(x,y) = g_x x + g_y y + \frac{1}{2}(H_{xx} x^2 + 2 H_{xy} xy + H_{yy} y^2).\]Note that we can write this as a linear function of \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}^T = [g_x, \ g_y, \ H_{xx}, \ H_{yy}, \ H_{xy}]\). Hence, letting \(\phi(\mathbf p)^T = [x, \ y, \ (1/2) x^2, \ (1/2)y^2, \ xy]\), we have the linear function \(m_k(\mathbf p) = \phi(\mathbf p)^T \boldsymbol{\alpha}.\) This gives rise to a Vandermonde system to find the interpolating polynomial coefficients. We solve the following equation for \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\):

\[\begin{bmatrix} \rule{1cm}{0.4pt} & \phi(\mathbf p_1)^T & \rule{1cm}{0.4pt} \\ \rule{1cm}{0.4pt} & \phi(\mathbf p_2)^T & \rule{1cm}{0.4pt} \\ & \vdots & \\ \rule{1cm}{0.4pt} & \phi(\mathbf p_m)^T & \rule{1cm}{0.4pt} \end{bmatrix} \boldsymbol{\alpha} = \mathbf f,\]where \(\mathbf{f}\) is a vector of centered function values for the current iteration \(k\), i.e., \((\mathbf f)_j = f(\mathbf p_j)-f(\mathbf p_k)\). We let \(\mathbf V\) represent the matrix composed of \(\phi\)’s. We generally split \(\mathbf V\) into two separate matrices corresponding to the linear and quadratic components such that \([\mathbf L, \ \mathbf Q] = \mathbf V\) and \([\mathbf g^T, \ \mathbf h^T] = \boldsymbol{\alpha}\). We rewrite the Vandermonde system as

\[\mathbf L \mathbf g + \mathbf Q \mathbf h = \mathbf f_k.\]It is easily seen that this same formulation will extend to higher dimension with \(\mathbf L\) being the linear weights, the first \(n\) components of \(\mathbf h\) corresponding the diagonal terms of the quadratic polynomial Hessian, and the remainder corresponding to the cross-terms.

Underdetermined system

To have a unique solution for the Vandermonde system above, there must be an equal number of interpolating conditions to the number of coefficients in the polynomial. For high-dimensional problems we often have many more variables than constraints. In such cases, we can recover a unique solution by solving them minimum norm problem, i.e.,

\[\min_{\mathbf h} \qquad \qquad \frac{1}{2} \|\mathbf h \|^2 \\ \text{subject to} \quad \mathbf L \mathbf g + \mathbf Q \mathbf h= \mathbf f_k.\]Hermite interpolation for trust regions

Although we do not observe the gradient on every iteration, we have occasional access. When available, we would like to use the gradient information to help improve the model. Hermite interpolation is a method designed to match function and derivative values as well. In one-dimension, we can fit a line with two points or alternately use a function value and function derivative. That is, the points \((x_1, f(x_1))\) and \((x_2, f(x_2))\) specifies a line as does \((x_1, f(x_1))\) and \((x_1, f'(x_1))\) with the latter, incidentally, corresponding to the linear Taylor expansion.

Borrowing ideas from one-dimensional Hermite interpolation, we can fit gradients which provide \(n\) additional constraints to improve our model. Simple calculus shows that

\[\nabla m_k(\mathbf p) = \mathbf g + \mathbf{H \ p} = \nabla f(\mathbf x_k + \mathbf p).\]This can be rewritten with an augmented Vandermonde system,

\[\begin{bmatrix} \mathbf L \\ \mathbf I \end{bmatrix} \mathbf g + \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf Q\\ \mathbf D_j \end{bmatrix} \mathbf h = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf f \\ \nabla f(\mathbf x_j) \end{bmatrix},\]where \(\mathbf I\) is the identity matrix and \(D_j\) is the Jacobian (derivative) of the vector \(\phi(\mathbf{x})\) at \(\mathbf x = \mathbf x_j\). More derivatives can be added but there are limits based on the degree of the polynomial for the system to remain consistent. In ongoing work, we are investigating how to exploit derivative information to improve interpolation based TR methods.