This section is based on my Masters thesis completed while at Texas State. It’s been my intention for several years now to submit this work to a journal, but for the time being, this page will have to suffice.

Background

Partial differential equations (PDEs) lay the foundation for the physical sciences and many engineering disciplines. We focus our attention here on Poisson’s Equation, an elliptic PDE given by

\[\begin{align} \nabla^2 u(x) & = f(x), \qquad x \in \Omega, \\ u(x) & = g(x), \qquad x \in \partial \Omega, \end{align}\]where \(\Omega\) is the interior of some domain and \(\partial \Omega\) is its boundary. Unfortunately, most PDEs can’t be solved analytically. This limitation necessitates approximate solutions to these systems.

To simplify the problem, rather than solving the PDE on a continuum, \(\Omega\) is discretized to a finite number of points and a solution is found that satisfies the equation on this constrained or projected set. The discretized PDE is written as

\[\begin{align} \nabla_h^2 u(x) & = f(x), \qquad x \in \Omega_h, \\ u(x) & = g(x), \qquad x \in \partial \Omega_h. \end{align}\]The subscript denotes the discretized operator and domain. For those of you unfamiliar with numerical PDEs, a natural question is how one finds a discretized operator?

A classical method for discretizing and solving PDEs numerically is the finite difference method (FDM). The basic idea is to use Taylor expansions to approximate differential operators. For illustrative purposes, consider the one dimensional function \(f(x)\). To approximate \(f''(x)\), we Taylor expand \(f(x+h)\) and \(f(x-h)\) about \(x\). We call \(h\) our step size and write \(f(x), \ f(x+h)\) and \(f(x-h)\) as \(f_0, \ f_+\), and \(f_-\), respectively. We have

\[\begin{align} f_- & = f(x) - f'(x)h + \frac 1 2 f''(x)h^2 - \frac 1 6 f'''(x)h^3 + \frac 1 {24} f^{(4)}(x)h^4 + \dots _, \\ f_0 & = f(x)_, \\ f_+ & = f(x) + f'(x)h + \frac 1 2 f''(x)h^2 + \frac 1 6 f'''(x)h^3 + \frac 1 {24} f^{(4)}(x)h^4 + \dots _. \end{align}\]Adding the first and third equation and subtracting two times the second gives

\[f_- \ -\ 2f_0 \ +\ f_+ = f''(x) h^2 + \frac 1 {12} f^{(4)}(x) h^4 + \dots,\]which we rearrange to give

\[f''(x) = \frac{ f_ \ - \ 2f_0 \ + \ f_+}{h^2} + \mathcal{O}(h^2).\]When \(h\) is taken to be small, the approximation

\[f''(x) \approx \frac{f(x-h) - 2f(x) + f(x+h)}{h^2}\]holds well. The above expression is known as the three point FDM approximation to the second derivative. Of particular note is that the truncation error, which tells how inaccurate our solution is, scales with \(h^2\), i.e., the smaller the step size, the more accurate the approximation. The square suggests that when we halve our step size, the approximation’s error reduces by a factor of 4.

In the above expansion, we benefited from the symmetry in step sizes. Since \(f_-\) and \(f_+\) are a distance of \(h\) away from the expansion point, the 1st and 3rd derivative terms dropped out. Consequently, the dominate error term came from the fouther derivative or the \(h^2\) term. What happens when the mesh is not spaced uniformly?

Non-Uniform Meshes

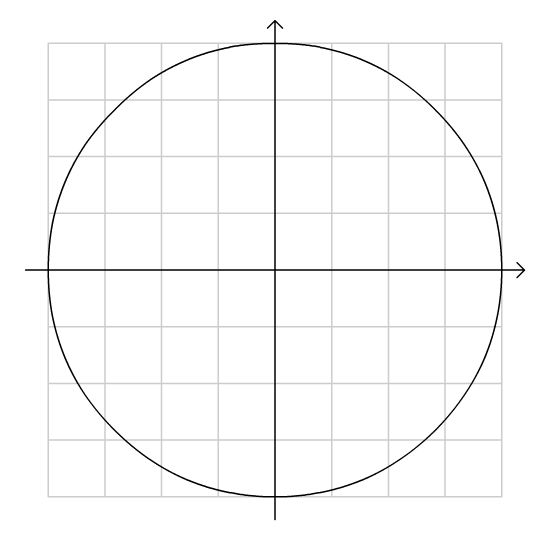

We now consider the case where the left and right step sizes are different. In the above case, a naive error analysis suggests that the truncation error varies as \(\mathcal O (h)\) rather then \(\mathcal O (h^2)\) owing to the 3rd derivative term. One reason to use an irregular mesh is when the boundary exhibits non-standard geometry. This becomes a concern for simple problems such as using a Cartesian mesh on a circular domain. Since the boundary elements are irregularly spaced from interior mesh points, an asymmetric mesh must be used as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Cartesian mesh on circular domain necessitating irregular grid.

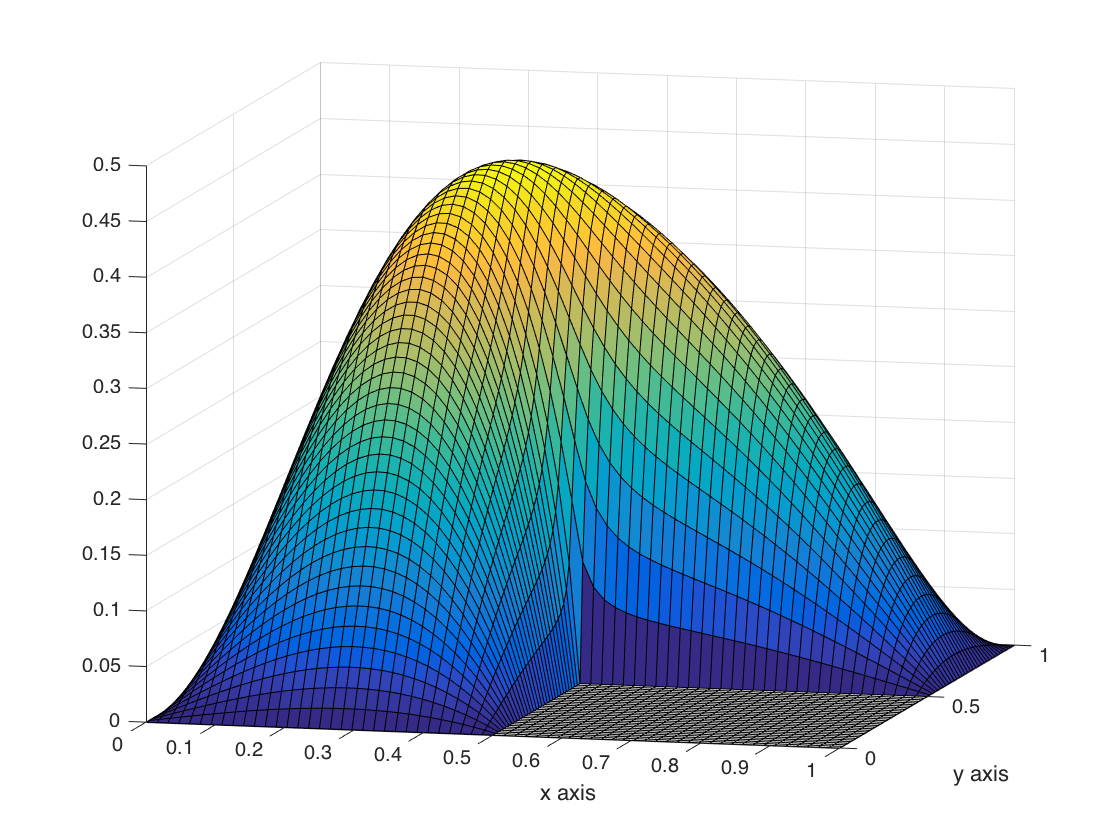

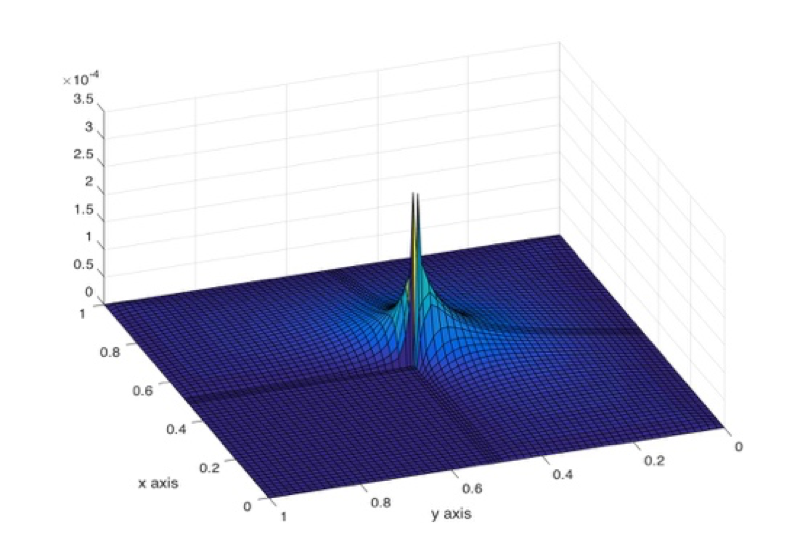

Another use for non-uniform meshes is increased resolution in regions where the solution’s behavior exhibits interesting properties. A prototypical example is Poisson’s equation with \(f(x) = -1\) in \(\Omega\) and \(g(x) = 0\) on \(\partial \Omega\) where \(\Omega\) is a recalcitrant square or flag-shaped domain. The numerical solution and its error is show in Figure 2. By introducing a finer mesh, the numerical error can be effectively tamped down locally.

Figure 2: Solution to Poisson's equation over a flag-shaped domain (left) and the corresponding numerical error (right). Note that solution and error are viewed from different perspectives.

Improved Truncation Error

In this thesis, I extended the work of Bramble and Hubbard1 to show that the truncation error \(\epsilon(x,y)\) for the two dimensional Poisson equation with Dirichlet boundary conditions is upper bounded by

\(|\epsilon(x,y)| \le \frac{2h^2}{3} \left\{ \frac{d_0^2 M_4}{64} + M_3 \left[ h + \frac{d_X^2 + d_Y^2}{(O_X^2 + O_X^{\ })^{-1} + (O_Y^2 + O_Y^{\ })^{-1}} \right] \right\}\) where

- \(h\) is the largest step size,

- \(M_3, \ M_4\) are the largest 3rd and 4th derivatives, respectively,

- \(d_0\) is the diameter of the smallest circle enclosing the domain,

- \(d_X, \ d_Y\) are the width and height of smallest rectangle containing the domain,

- \(O_X, \ O_Y\) are the number of non-uniform mesh points in the \(x\) and \(y\) directions, respectively.

Details on the particulars can be found here.

-

Bramble, James H., and B. E. Hubbard. On the formulation of finite difference analogues of the Dirichlet problem for Poisson’s equation. MARYLAND UNIV COLLEGE PARK INST FOR FLUID DYNAMICS AND APPLIED MATHEMATICS, 1961. ↩